Publishers should be thanking modders for making their old games playable

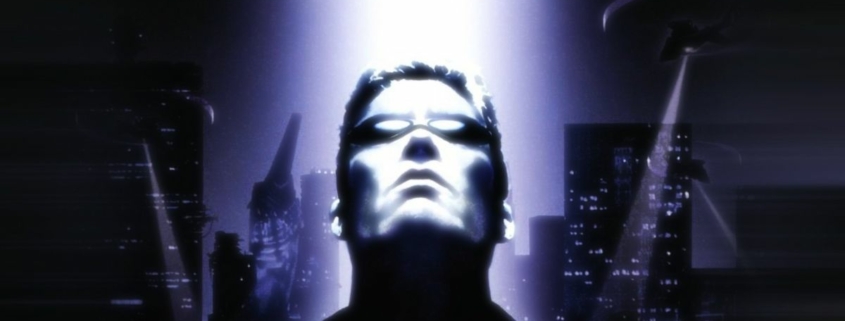

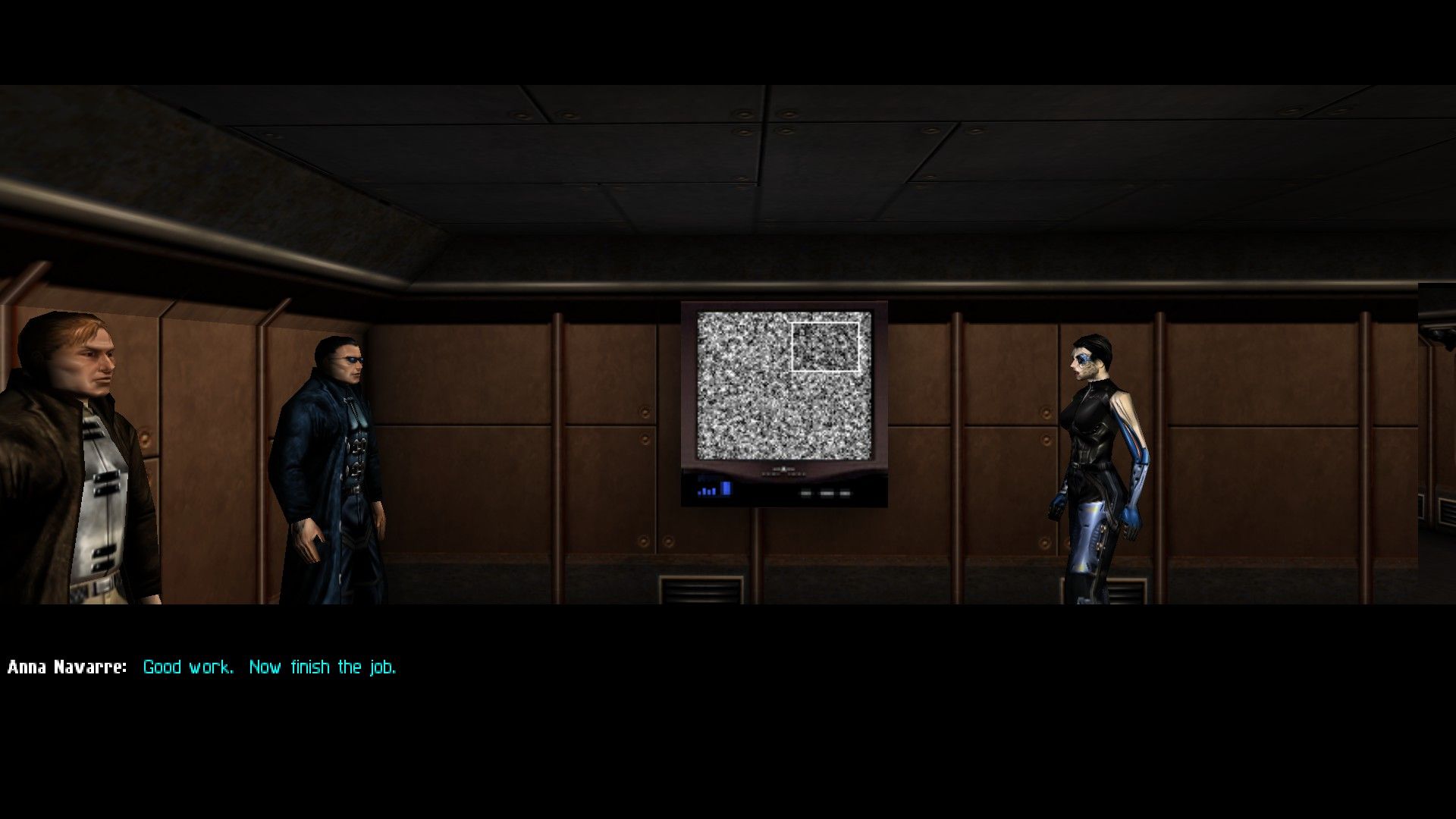

Deus Ex is a game stuffed with essential dialogue—political philosophy from Ion Storm firebrand Sheldon Pacotti, and lifesaving advice from your big brother Paul Denton. And so a rendering bug that skipped the last four or five words of every line proved practically game-breaking when I booted up the classic shooter-RPG for another playthrough on its 20th anniversary.

“Some say concentrated power leads to abuse, but I believe that if an institution has a solid foundation it can survive the narrow aspirations of—”

“It’s only a matter of time before someone clever and ambitious figures out that the tools of dictatorship have been ready-made by—”

“A nonlethal takedown is always the most silent way to—”

A quick google brought me to a Steam forum thread, where veterans recommended editing .ini files in the bowels of the game to solve the problem. It all looked a little gnarly. “Or,” read one reply, “you could just use kenties launcher”.

Kentie’s Launcher (opens in new tab), or Deus Exe, turned out to be an all-in-one compatibility fix that came bundled with a configuration menu and mod manager. I installed it, and played Deus Ex happily for dozens of hours afterwards.

It’s a story that’s played out with only slight variations multiple times on my PC. Arx Fatalis, the first ever Arkane game, only became playable once I downloaded the open source engine Arx Libertatis (opens in new tab). And before Quake’s recent remaster, the unofficial engine Quakespasm (opens in new tab) was the best way to see its gothic halls on a modern machine. Yet no compatibility issues are mentioned on the official pages of these games on Steam, where all three are currently lining the pockets of their publishers.

Perhaps it’s too much to ask the likes of Square Enix and Bethesda to maintain decades-old products they acquired with their parent studios. But surely a thank you to those modders who’ve kept their classic games alive wouldn’t go amiss.

Fixer upper

Kentie—full name Marijn Kentie, now a 36-year-old programmer who creates software used to automate bridge processes on dredgers at sea—has never thought about his work on Deus Ex as an unpaid support role.

“I was just happy to teach myself something and be able to play the game,” he says. “And also, of course, allow others to play it. I don’t really feel like there’s any injustice in that I have to support a game someone else is selling. However, I do have to admit that the actual support part isn’t my favourite—answering emails from people, or trying to track down issues they have with their systems.”

I was just happy to teach myself something and be able to play the game.

At a certain point, trawling through a player’s log files or installing different driver versions to nail down their problem begins to feel more like work than a hobby. “But that’s the risk you take by putting something out there for people to use,” Kentie says. “I’ve never thought, ‘I wish the publisher would contact me or pay me.’ Although it is kind of strange how many games are sold without any fixes, or use a lazily included version of DOSBox.”

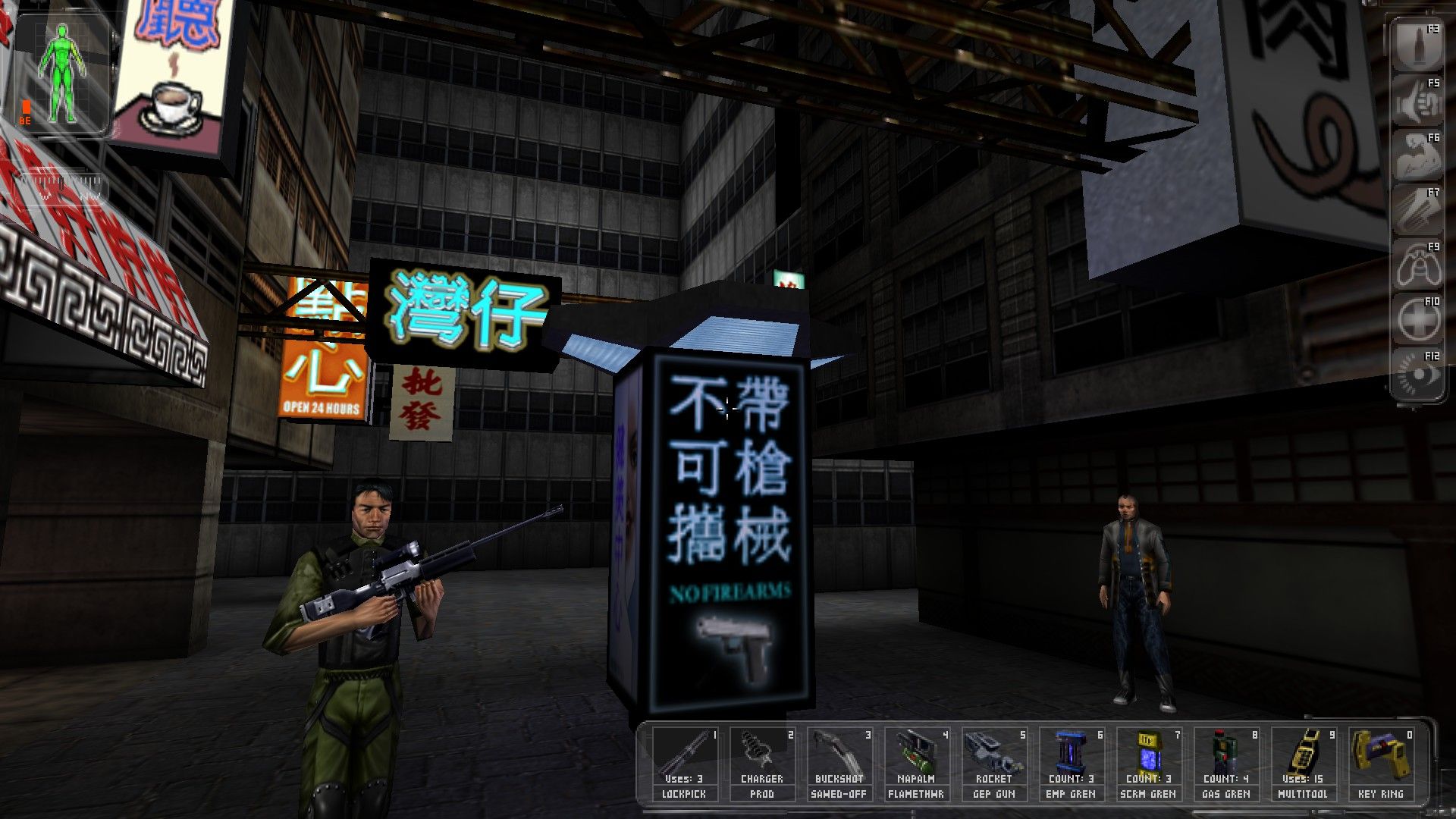

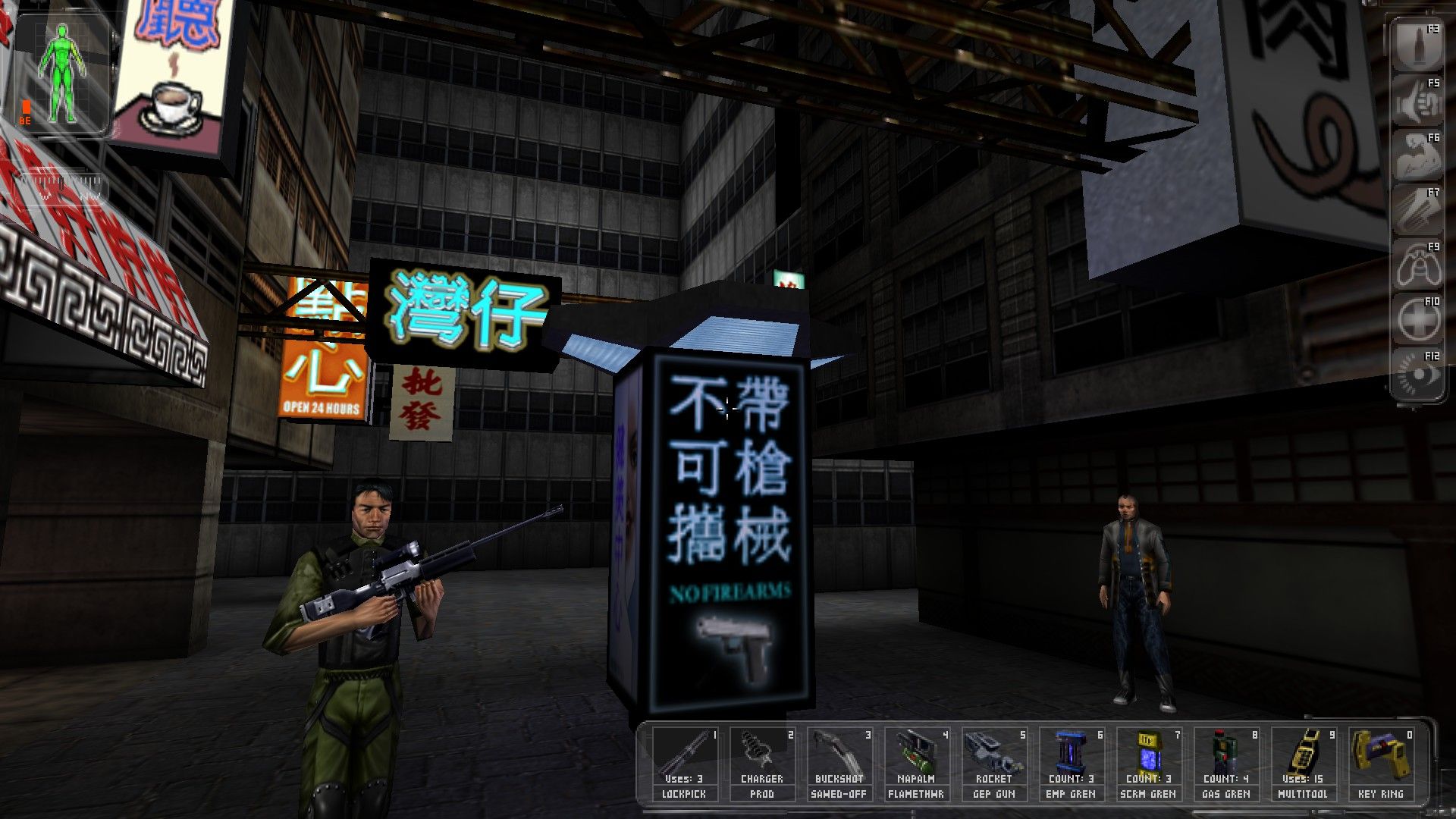

Kentie first put together his launcher in his 20s, during free time between courses at college. “Deus Ex was, or is, my favourite game of all time,” he says. “So I really wanted to be able to play it well. It was released at a time when developments in computer hardware were still going a bit faster. It was really geared towards the tail end of the Windows 98 and 3dfx cards era, and compatibility with Windows XP, multicore processors and newer video cards wasn’t that great. My favourite game was getting difficult to play in a way that replicated the original experience.”

The Kentie Launcher includes an alternative renderer—and although it’s now 15 years old, it hasn’t needed tweaking too regularly as the rate of change in computer hardware has slowed down. Most of the more recent issues have been related to graphics card drivers. “Those are very annoying,” Kentie says. “You change something, and then that fixes the game, for reasons that aren’t really clear.”

A time for giving

Despite being a hobbyist, Kentie has had a front row seat to the rise of digital distribution and the consequent commercial comeback of classic PC games. Whenever Deus Ex entered a Steam sale, he would notice an uptick in both downloads of his launcher and questions from users.

He points out that resources like the Steam Community, where players collect and curate information on mods and fixes, didn’t exist when he first became involved in modding in the late noughties: “People had more personal, simple websites where they said, ‘Here’s the mod I made.'”

Making the launcher was Kentie’s way of giving back—an expression of gratitude to others who had made similar compatibility projects available for free online. “I had to put something out there myself,” he says, “to pay it forward.”

Today, he’s circumventing the same problems he once solved in a different way—playing old games on their original hardware. In the last couple of years, he’s set up a PC using old parts to play the original Doom “as it was meant”.

“That’s nice, but I also realise that not everyone can play the game like that—you need to have old crap lying around, or be able to find or buy it,” he says. “Some of it is really expensive. So I do think it’s very important that there’s a way to preserve games on modern systems as they were meant to be played. It’s an interesting hobby, to get those old computers going, but I really like that there are efforts for people, including myself, to be able to just start something and play like it was back in the day, in an easy way.”

Deus Ex is a game stuffed with essential dialogue—political philosophy from Ion Storm firebrand Sheldon Pacotti, and lifesaving advice from your big brother Paul Denton. And so a rendering bug that skipped the last four or five words of every line proved practically game-breaking when I booted up the classic shooter-RPG for another playthrough on its 20th anniversary.

“Some say concentrated power leads to abuse, but I believe that if an institution has a solid foundation it can survive the narrow aspirations of—”

“It’s only a matter of time before someone clever and ambitious figures out that the tools of dictatorship have been ready-made by—”

“A nonlethal takedown is always the most silent way to—”

A quick google brought me to a Steam forum thread, where veterans recommended editing .ini files in the bowels of the game to solve the problem. It all looked a little gnarly. “Or,” read one reply, “you could just use kenties launcher”.

Kentie’s Launcher (opens in new tab), or Deus Exe, turned out to be an all-in-one compatibility fix that came bundled with a configuration menu and mod manager. I installed it, and played Deus Ex happily for dozens of hours afterwards.

It’s a story that’s played out with only slight variations multiple times on my PC. Arx Fatalis, the first ever Arkane game, only became playable once I downloaded the open source engine Arx Libertatis (opens in new tab). And before Quake’s recent remaster, the unofficial engine Quakespasm (opens in new tab) was the best way to see its gothic halls on a modern machine. Yet no compatibility issues are mentioned on the official pages of these games on Steam, where all three are currently lining the pockets of their publishers.

Perhaps it’s too much to ask the likes of Square Enix and Bethesda to maintain decades-old products they acquired with their parent studios. But surely a thank you to those modders who’ve kept their classic games alive wouldn’t go amiss.

Fixer upper

Kentie—full name Marijn Kentie, now a 36-year-old programmer who creates software used to automate bridge processes on dredgers at sea—has never thought about his work on Deus Ex as an unpaid support role.

“I was just happy to teach myself something and be able to play the game,” he says. “And also, of course, allow others to play it. I don’t really feel like there’s any injustice in that I have to support a game someone else is selling. However, I do have to admit that the actual support part isn’t my favourite—answering emails from people, or trying to track down issues they have with their systems.”

I was just happy to teach myself something and be able to play the game.

At a certain point, trawling through a player’s log files or installing different driver versions to nail down their problem begins to feel more like work than a hobby. “But that’s the risk you take by putting something out there for people to use,” Kentie says. “I’ve never thought, ‘I wish the publisher would contact me or pay me.’ Although it is kind of strange how many games are sold without any fixes, or use a lazily included version of DOSBox.”

Kentie first put together his launcher in his 20s, during free time between courses at college. “Deus Ex was, or is, my favourite game of all time,” he says. “So I really wanted to be able to play it well. It was released at a time when developments in computer hardware were still going a bit faster. It was really geared towards the tail end of the Windows 98 and 3dfx cards era, and compatibility with Windows XP, multicore processors and newer video cards wasn’t that great. My favourite game was getting difficult to play in a way that replicated the original experience.”

The Kentie Launcher includes an alternative renderer—and although it’s now 15 years old, it hasn’t needed tweaking too regularly as the rate of change in computer hardware has slowed down. Most of the more recent issues have been related to graphics card drivers. “Those are very annoying,” Kentie says. “You change something, and then that fixes the game, for reasons that aren’t really clear.”

A time for giving

Despite being a hobbyist, Kentie has had a front row seat to the rise of digital distribution and the consequent commercial comeback of classic PC games. Whenever Deus Ex entered a Steam sale, he would notice an uptick in both downloads of his launcher and questions from users.

He points out that resources like the Steam Community, where players collect and curate information on mods and fixes, didn’t exist when he first became involved in modding in the late noughties: “People had more personal, simple websites where they said, ‘Here’s the mod I made.'”

Making the launcher was Kentie’s way of giving back—an expression of gratitude to others who had made similar compatibility projects available for free online. “I had to put something out there myself,” he says, “to pay it forward.”

Today, he’s circumventing the same problems he once solved in a different way—playing old games on their original hardware. In the last couple of years, he’s set up a PC using old parts to play the original Doom “as it was meant”.

“That’s nice, but I also realise that not everyone can play the game like that—you need to have old crap lying around, or be able to find or buy it,” he says. “Some of it is really expensive. So I do think it’s very important that there’s a way to preserve games on modern systems as they were meant to be played. It’s an interesting hobby, to get those old computers going, but I really like that there are efforts for people, including myself, to be able to just start something and play like it was back in the day, in an easy way.”