TV showrunners and game developers have become allies at long last

Watching the trailer for HBO’s The Last of Us is a frankly eerie experience. For years, videogame fans have grown used to scouring early footage of TV and movie adaptations for familiar details; small hints that might signify real fondness for the source material. But here, the resemblance is uncanny and everywhere. Even in live action, The Last of Us is instantly recognisable in its high-rise greenery and rooftop plank walks; its horseback rides and morose car journeys along quiet highways with Ellie in the passenger seat; the triggering sound of the clickers, halfway between a Geiger counter and the spinning rattles at a 1960s football match. Even the familiar font of the logo, with the stubby tail to its ‘L’, is present and correct.

In one sense, it’s no surprise. Those who’ve followed the prestige drama’s development closely will know that the fastidious screenwriter behind Chernobyl, Craig Mazin, shares showrunner status with Naughty Dog’s Neil Druckmann. Never before has a game’s creator been so closely involved with its adaptation for television. Yet it’s still surreal to wake up in an era where showrunners and game developers are finally working together, for mutual benefit.

It serves no one to pick through the rubble of failed adaptations past—at the time, the television and movie industry’s disrespect for the younger mediums of videogames and comic books reflected a common feeling in mainstream Western culture. Only now do an upper echelon of game studios have the cachet to dictate the terms under which their work is translated, and command sufficient respect from screenwriters to engage in meaningful collaboration.

Edge case

Many developers will be seeking to follow the model of CD Projekt Red. On the one hand, the studio’s close supervision of the Netflix anime Cyberpunk: Edgerunners has resulted in a one-to-one recreation of Night City reminiscent of HBO’s The Last of Us; on the other, it hasn’t required the donation of a game director like Druckmann, and the consequent loss of creative bandwidth that would entail. Instead, CDPR appointed its own comic book and animation director, Bartosz Sztybor, as a writer and producer on Edgerunners—and picked out an anime partner clearly in love with its game. Tokyo’s Studio Trigger asked for a save file in which they could free-roam CD Projekt Red’s game world, and cruised Night City as if scouting for locations—taking photos in every district in order to capture the minutiae, as well as soak up the environmental storytelling.

“The theme of social inequality and violence, which instills fear in us even in the real world, is depicted in great detail in the game,” says Studio Trigger co-founder Masahiko Otsuka in a Netflix making-of. “We made sure to focus on these themes in the anime as well.”

Edgerunners required a much smaller investment from CDPR than a Cyberpunk expansion or sequel might, but brought immediate dividends. After the show’s hugely successful launch on Netflix, the developer secreted references into its parent game in an Edgerunners update, and enjoyed “visibly affected unit sales”. The anime helped CDPR reach its best financial quarter ever, and perhaps more importantly went some of the distance to restoring the studio’s damaged reputation. Quest director Paweł Sasko took to Twitter to emotionally thank the tens of thousands of new players who had left ‘Very Positive’ user reviews on Steam—an unimaginable scene when Cyberpunk 2077 launched back in 2020.

Last days #Cyberpunk2077 received a flood of very positive reviews on Steam from the new players 🥺You can’t imagine what it means to me 🥺 pic.twitter.com/bz3xElKixTNovember 25, 2021

Witcher’s brew

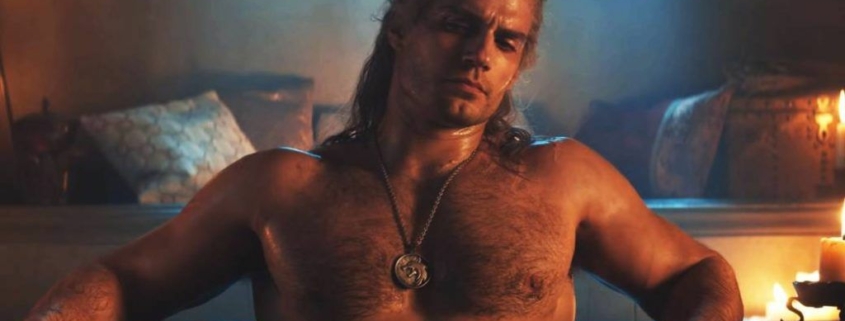

Of course, there’s more than one way to show respect for the material, as evidenced by CD Projekt and Netflix’s other shared big hitter, The Witcher. Counterintuitively, Lauren Schmidt Hissrich’s show has succeeded by keeping its distance from the games.

When Hissrich first described her series as an adaptation of the Witcher novels, rather than the games which had popularised Andrzej Sapkowski’s stories outside of Poland, fans interpreted her comments as a snub. But in reality, the clear space between CDPR’s stories and the Netflix show has made them perfect companion pieces. Consciously or not, a temporal dividing line has been drawn. Since the events of the Witcher games all take place after the conclusion of the novels, Hissrich’s writing team has been free to reinterpret Sapkowski’s writing as needed without accidentally rearranging CDPR’s furniture.

As a viewer, it’s all upside. None of the choices you might make on Geralt’s behalf in Wild Hunt are negated by the plot of the show. And seeing the background of characters like Ciri and Triss explored on TV only deepens your emotional understanding of who you’re dealing with in the games.

Where Netflix has expanded on the books, it’s delved further into the past of its central cast, rather than meddled with their gaming future. When the show extrapolated an entire origin story for Yennefer from Sapkowski’s scattered mentions of spinal deformity and a miserable education at Aretuza, fans of The Witcher 3 were grateful. Finally they had a true sense of what drove the woman they’d been chasing across the continent, and what connected her to Geralt (either their stolen childhoods or a genie’s wish, depending on who you ask).

Canon fire

This month’s Blood Origin spin-off takes a similar approach, in that it concerns 1,000-year-old history—an era of the Witcher world that CDPR has never messed with in canonical fashion, and likely never will. Even if, as early whispers suggest, it’s not quite up to snuff, Blood Origin’s archival nature means it’ll be easy for gaming fans to take or leave as they see fit.

Then there’s Arcane: League of Legends—the Netflix adaptation supervised by Riot Games that tells a relationship-driven story its parent game never could in the course of a 40-minute MOBA match. After the show dethroned Squid Game to become Netflix’s most-watched series at the time, pick rates for LoL champions Jayce and Jinx spiked as players suddenly saw something new in them.

Marvel’s Midnight Suns, meanwhile, has pulled the opposite trick—helping to revive half-forgotten Hulu series The Runaways by having actress Lyrica Okano reprise her role as Nico Minoru, a central figure in the Suns. There’s a sense that devs and TV writers alike are finally looking for opportunities to lift each other up.

Perhaps showrunners are discovering, too, that the best adaptations don’t really adapt. Instead, they tell the stories that developers won’t or can’t tell in an interactive framework, enriching beloved worlds by playing to serialised television’s strengths, rather than mimicking another medium entirely. Mind you: we’ll always have a soft spot for that bit in the Doom movie that goes first-pers

Watching the trailer for HBO’s The Last of Us is a frankly eerie experience. For years, videogame fans have grown used to scouring early footage of TV and movie adaptations for familiar details; small hints that might signify real fondness for the source material. But here, the resemblance is uncanny and everywhere. Even in live action, The Last of Us is instantly recognisable in its high-rise greenery and rooftop plank walks; its horseback rides and morose car journeys along quiet highways with Ellie in the passenger seat; the triggering sound of the clickers, halfway between a Geiger counter and the spinning rattles at a 1960s football match. Even the familiar font of the logo, with the stubby tail to its ‘L’, is present and correct.

In one sense, it’s no surprise. Those who’ve followed the prestige drama’s development closely will know that the fastidious screenwriter behind Chernobyl, Craig Mazin, shares showrunner status with Naughty Dog’s Neil Druckmann. Never before has a game’s creator been so closely involved with its adaptation for television. Yet it’s still surreal to wake up in an era where showrunners and game developers are finally working together, for mutual benefit.

It serves no one to pick through the rubble of failed adaptations past—at the time, the television and movie industry’s disrespect for the younger mediums of videogames and comic books reflected a common feeling in mainstream Western culture. Only now do an upper echelon of game studios have the cachet to dictate the terms under which their work is translated, and command sufficient respect from screenwriters to engage in meaningful collaboration.

Edge case

Many developers will be seeking to follow the model of CD Projekt Red. On the one hand, the studio’s close supervision of the Netflix anime Cyberpunk: Edgerunners has resulted in a one-to-one recreation of Night City reminiscent of HBO’s The Last of Us; on the other, it hasn’t required the donation of a game director like Druckmann, and the consequent loss of creative bandwidth that would entail. Instead, CDPR appointed its own comic book and animation director, Bartosz Sztybor, as a writer and producer on Edgerunners—and picked out an anime partner clearly in love with its game. Tokyo’s Studio Trigger asked for a save file in which they could free-roam CD Projekt Red’s game world, and cruised Night City as if scouting for locations—taking photos in every district in order to capture the minutiae, as well as soak up the environmental storytelling.

“The theme of social inequality and violence, which instills fear in us even in the real world, is depicted in great detail in the game,” says Studio Trigger co-founder Masahiko Otsuka in a Netflix making-of. “We made sure to focus on these themes in the anime as well.”

Edgerunners required a much smaller investment from CDPR than a Cyberpunk expansion or sequel might, but brought immediate dividends. After the show’s hugely successful launch on Netflix, the developer secreted references into its parent game in an Edgerunners update, and enjoyed “visibly affected unit sales”. The anime helped CDPR reach its best financial quarter ever, and perhaps more importantly went some of the distance to restoring the studio’s damaged reputation. Quest director Paweł Sasko took to Twitter to emotionally thank the tens of thousands of new players who had left ‘Very Positive’ user reviews on Steam—an unimaginable scene when Cyberpunk 2077 launched back in 2020.

Last days #Cyberpunk2077 received a flood of very positive reviews on Steam from the new players 🥺You can’t imagine what it means to me 🥺 pic.twitter.com/bz3xElKixTNovember 25, 2021

Witcher’s brew

Of course, there’s more than one way to show respect for the material, as evidenced by CD Projekt and Netflix’s other shared big hitter, The Witcher. Counterintuitively, Lauren Schmidt Hissrich’s show has succeeded by keeping its distance from the games.

When Hissrich first described her series as an adaptation of the Witcher novels, rather than the games which had popularised Andrzej Sapkowski’s stories outside of Poland, fans interpreted her comments as a snub. But in reality, the clear space between CDPR’s stories and the Netflix show has made them perfect companion pieces. Consciously or not, a temporal dividing line has been drawn. Since the events of the Witcher games all take place after the conclusion of the novels, Hissrich’s writing team has been free to reinterpret Sapkowski’s writing as needed without accidentally rearranging CDPR’s furniture.

As a viewer, it’s all upside. None of the choices you might make on Geralt’s behalf in Wild Hunt are negated by the plot of the show. And seeing the background of characters like Ciri and Triss explored on TV only deepens your emotional understanding of who you’re dealing with in the games.

Where Netflix has expanded on the books, it’s delved further into the past of its central cast, rather than meddled with their gaming future. When the show extrapolated an entire origin story for Yennefer from Sapkowski’s scattered mentions of spinal deformity and a miserable education at Aretuza, fans of The Witcher 3 were grateful. Finally they had a true sense of what drove the woman they’d been chasing across the continent, and what connected her to Geralt (either their stolen childhoods or a genie’s wish, depending on who you ask).

Canon fire

This month’s Blood Origin spin-off takes a similar approach, in that it concerns 1,000-year-old history—an era of the Witcher world that CDPR has never messed with in canonical fashion, and likely never will. Even if, as early whispers suggest, it’s not quite up to snuff, Blood Origin’s archival nature means it’ll be easy for gaming fans to take or leave as they see fit.

Then there’s Arcane: League of Legends—the Netflix adaptation supervised by Riot Games that tells a relationship-driven story its parent game never could in the course of a 40-minute MOBA match. After the show dethroned Squid Game to become Netflix’s most-watched series at the time, pick rates for LoL champions Jayce and Jinx spiked as players suddenly saw something new in them.

Marvel’s Midnight Suns, meanwhile, has pulled the opposite trick—helping to revive half-forgotten Hulu series The Runaways by having actress Lyrica Okano reprise her role as Nico Minoru, a central figure in the Suns. There’s a sense that devs and TV writers alike are finally looking for opportunities to lift each other up.

Perhaps showrunners are discovering, too, that the best adaptations don’t really adapt. Instead, they tell the stories that developers won’t or can’t tell in an interactive framework, enriching beloved worlds by playing to serialised television’s strengths, rather than mimicking another medium entirely. Mind you: we’ll always have a soft spot for that bit in the Doom movie that goes first-pers